january  2015

2015

I had a minor epiphany during a disaster movie marathon I undertook over the holidays to curb the withdrawal symptoms from The Walking Dead's 6-month mid-season fuck off. I was watching The Tower, a 2012 big budget South Korean remake of the 1974 classic Towering Inferno when I realized that, with few exceptions, disaster movies are about economic inequality.

Any disaster large enough in scale to bother making a movie about it naturally brings together people from all different economic strata. When The Titanic fell through a hole in the ocean to its final resting place two miles below the surface, the icy waters of the North Atlantic met its steerage stowaways with the same crushing embrace as its gilded age industrialists. And the molten rock that rained down from Mount Vesuvius on Pompeii and Herculaneum didn't discriminate between the upper crust and their serving maids. Their volcanically entombed remains would be preserved together until modern day scientists came along to unearth their stories.

Every disaster movie addresses this trope, usually in a single scene—the long-suffering second-class citizens confront their erstwhile oppressors when an "act of god" levels the playing field—and sometimes the entire movie becomes a morality play about haves vs. have-nots (again, think Titanic and Pompeii). The message is that catastrophe is the great leveler in more ways than one. Well... catastrophe and hubris.

Because of course, the earliest known disaster stories—The Epic of Gilgamesh (circa ~2,000 BC) and Plato's account of the destruction of Atlantis (360 BC)—were cautionary tales about how human overreach into realms of the divine invited the wrath of the gods. But modern-day parables are set in a godless age—or an age after god, if you will. We are still fearful creatures in need of cautionary tales, and we still fear the superhuman powers which were once attributed to the gods, but now the capacity for cruelty, indifference and wanton, heedless destruction that we fear the most is our own.

Which brings us, of course, to zombies.

[Night of the Living Dead poster by Florian Bertmer,

whose amazing work I'd always thought of as a genre,

but I recently discovered it's all the work of one artist.]

Like the wider disaster genre, zombies tend to proliferate during troubled economic times, when civil society itself seems set to unravel. Patient Zero in the modern-day Zombie Apocalypse was George Romero's low budget masterpiece, Night of the Living Dead. It opened in theaters on October 1, 1968, a year that's remembered for many things, most of which have little to do with launching the defining genre of our time. (Caution: 50-year old spoilers ahead.)

In the United States, as in other parts of the world, 1968 was a year of shocking political assassinations and corruption, escalating atrocities in Vietnam, revolutions to the east and race riots and violent protests to the west. Almost by serendipity, the kids who comprised the audience for horror movies at the time were the same kids whose college campuses had become ground zero for government suppression. They were the same kids for whom "coming of age" was synonymous with conscription and the fear of being shipped to Vietnam to kill, perhaps to die, in a foreign jungle, at the whim of some old white men in their proverbial smoke-filled rooms.

Those same kids, throughout their adolescence, had seen the black and white news footage of police and National Guard soldiers beating civil rights activists, turning dogs and fire hoses on the beleaguered descendants of American slaves, the melanin in their very skin was itself an indelible reminder of what had previously been, until Vietnam anyway, the most ignominious chapter in the nation's bloody history. An entire impressionable generation grew up seeing civil rights activists beaten in the streets for marching peacefully, for daring to sit down at a lunch counter, or sending their children to attend public schools. The audience of 1968 knew that the stoic leaders in that struggle were now being systematically slain by the same old white men who were orchestrating the war in Vietnam.

Steeped in these inescapable visions, a generational conscience had emerged. Those who were not paralyzed by despair and helplessness were mobilized by an almost primordial rage against the ugliness, injustice and brutality of the world around them. Somehow all these events were symbolically encapsulated in this little, almost but not quite, laughably lowbrow film. To some, it seemed a perfectly apt metaphor for the times; a grotesque, horrifying parable—a funhouse mirror that reflected the true face of an even more grotesque and horrifying reality. And it came at the perfect time for its intended audience to receive that message.

In this parable, the switch that suddenly turns the dead against the living is never fully explained, only hypothesized as a possible side effect of radioactive fallout from a destroyed satellite. But the newscasters seem unreliable, and the scientists either deceitful or incompetent, and besides, it matters little when the zombies are piling up outside the farmhouse door. Much has been said about the fact that the zombies were mostly white, older and affluently dressed.

(With that one notable exception.)

George Romero has explained that the zombie demographics were simply an artifact of casting a low-budget horror movie in rural Pennsylvania in the mid-60s. Old white people were the ones who volunteered and, more importantly, provided the financial backing for the film, so they were the ones who got cast as zombies. Besides, any racial diversity would have been effectively erased by the white makeup and extreme lighting effect that results from filming the flood-lit countryside at night on a limited budget.

But anyway, a film isn't about what the director intends. It's about what the audience sees, and in this case, what they saw was the white establishment—old men in suits and women in their Sunday best—a Silent Majority, indeed—roused from an eternal, godless sleep to walk the cursed earth, kill everyone in their path and mercilessly feast on living flesh.

Romero has also said that the film was never written with a black male lead in mind. In fact, in the original script, the main character was a typical blue collar white guy, a truck driver with anger management issues. The decision to cast Duane Jones, a black man who radiated an almost aristocratic intelligence, was made at the 11th hour, based solely on the actor's superlative audition. If anything, according to Romero, his race was incidental...

But it made the impact of his death at the end of the film anything but.

According to IMDB, George Romero and screenwriter John A. Russo finished editing on April 4, 1968 and they took the original print and drove with it to New York that very evening to arrange a screening. They were in the car when they heard the news on the radio that Martin Luther King had been assassinated.

As a genre, birthed in the blood of a revolutionary era, zombies were symbolic of the deep feelings of alienation and betrayal between generations, races and classes in America. They epitomized the growing sense that some invisible point of no return had been reached, that something had been broken which might never be repaired. The film was criticized for its extreme, even wantonly excessive, depictions of cannibalism, dismemberment and all manner of gruesome murder. Audiences had seen nothing like it before.

Some accused the filmmakers of promoting cannibalism (note: that was Readers Digest) and labelled the movie "evil," which invited the logical rebuttal that it wasn't any worse than events taking place in Vietnam—women and children murdered, entire villages burned and the dead heaped in mass graves, naked children running terrified in the streets, their skin burned by Napalm. That was the real evil. Those things were actually happening, and these supposedly good Christian Americans were getting outraged about a movie?

The fact that this genre-defining meta-narrative was seeded in 1968 is more than perfect, given what that year has come to stand for in our cultural memory. Few can match the metaphoric gravity of the original, but every fictional work has something to say about the real world in which it was created. And if we thought that 1968 was a long, dark night of the soul, what do its modern-day descendants have to say about how far we've come as a society?

"When there's no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth."

The world has spawned a lot of zombies in the last 50 years. We've seen the debatable (and much-debated) advent of fast zombies, brain-eating zombies, wise-cracking zombies, stoner zombies, semi-domesticated zombies, genetically engineered bioweapon zombies, lovesick emo zombies and even smart zombies (because, after all—evolution?). Everything means something, but some things mean more than others.

George Romero set his 1978 sequel Dawn of the Dead in a shopping mall, it's been accepted as canon ever since that zombies have something to do with consumerism. (Get it, they mindlessly consume?) But it's impossible to make that interpretation backwards compatible with the original film, especially in light of the more obvious parallels to the war in Vietnam and the civil rights movement.

Subsequent zombie films have satirized consumerism, militarism, colonial exploitation of the third world, unscrupulous pharmaceutical companies and the diabolical ends they'll go to for a profit, and of course, the diabolical ends to which governments will go to exploit any crisis, even a planetary extinction-level crisis.

"It's the economy, stupid."

There is certainly a common thread in the zombie genre about America's role as the world's self-appointed SWAT team, its economic abundance-slash-excess, and the childishness with which it conducts itself in the world amongst older nations. But the dominant theme is one best illustrated by the 2014 series "Z Nation." It's this idea that in the absence of a just or vengeful or even simply attentive god, we humans have royally fucked everything up. We are all complicit, and not the earth, not even god, but we alone, will be the authors and the instruments of our own undoing.

This was metaphorically expressed in the first season finale of The Walking Dead: "We are all infected." We're all zombies-in-waiting. In the Zombie Apocalypse, nobody is innocent and everyone is expendable (except our alpha male leader, who we follow unquestioningly), everybody pitches in (but it's nothing like communism), and we're all capable of murder—in self-defense, to protect a loved one, for a secure place to sleep, for our peace of mind. Hell, if you look at us funny we'll probably kill you... but hey, we don't have to explain ourselves to you.

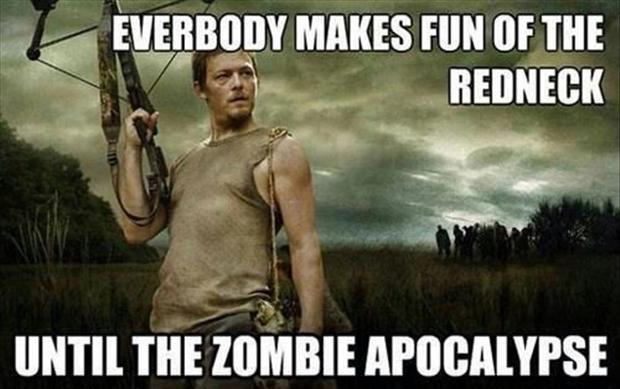

When The Walking Dead premiered on AMC in 2010, two years into the big "real estate bubble" recession, the show quickly established itself as a powerful antidote to the modern political and economic discourse. It may have been the End of America in the real world, maybe even the End of Men somewhere, but on AMC it was the end of the world and we felt fine.

Zombies clearly represent American fears of a world where they're not on top anymore; a fear that one day they'll wake up and find themselves working an 18-hour shift at the Foxconn plant. You will be assimilated. So we have persecution anxiety and its belligerent opposite; fuck multiculturalism and the global village. Just give us our guns, an endless supply of ammo and unlimited gasoline and we'll gladly forage for packaged non-perishables in the bombed-out shells of our once-great big box stores, and break into the homes of our former neighbors to raid their kitchens, make fun of their taste in art and put our feet up on their dining room tables.

In the same way that jazz was the first uniquely American music genre, zombies were the first uniquely American monster genre, and it's not incidental that they were an invention of the world's first adolescent superpower. God was pronounced dead and in response, Mary Shelly's Frankenstein asked the question, what kind of creators will we be now that we've taken his place? Zombies are the most secular of all our modern monsters, devoid of evil intent and divorced from any mythological origin—like the rogue asteroid that eliminates all life on earth in a single afternoon. But for modern atheists, even an asteroid looks too much like the wrath of god. We'll be the ones who decide when it's time to pull the plug on this little experiment called life on earth, thank you very much.

In fact, for the modern Zombie Apocalypse, no scientific cause is ever given. If they bother to float any theories at all, the consensus is usually that it was just the inevitable result of our tom-fuckery in realms we shouldn't have fucked with. Like AIDS and atom bombs, zombies are only the latest—and not all-that-surprising—blowback. We had it coming.

We are the 1%.

Every fictional genre can arguably be labeled "escapism," as if the only reason people are watching is so they can imagine themselves transported to a world without any problems. It could also be argued that every fictional reality is by definition about "simpler times" because its characters are two-dimensional constructs enacting a narrative with a fixed beginning and end... albeit, some more than others.

At the peak of American civilization in the early 1960s, when the US was at the top of the economic food chain and everyone dressed like characters from Mad Men, do you know what everyone was watching on TV? Westerns. More than half the top-rated shows between 1955 and 1965 were Westerns like Bonanza, Gunsmoke, Rawhide, The Rifleman and Have Gun, Will Travel—which, come to think of it, has to be the best name for an American TV show ever.

It makes you wonder just what kind of Bizarro World retrogressive libertarian fantasies are being lived out vicariously by fans of The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones (oh yes, I said it). Tempting though it might be to analyze this phenomenon away as wish fulfillment for a simpler, stupider, "shoot first, ask questions later" time, I don't think anyone watching these shows actually believes that life in the Zombie Apocalypse or the rapey, decapitate-y Middle Ages would be in any way preferable to our boring, predictable modern lives of freedom, convenience and a life expectancy over 40. (Not the women who watch them anyway).

(For the record, I never bought into the idea that shows like CSI were super-popular among Republicans either, just because the cops were all-powerful and could do anything to get a confession. I mean, yes, there was that, but at least all the people they bent the rules to put away were guilty anyway, right—not like in real life. Because the stories never ended with the confession, but with DNA evidence proving them guilty, and what's so Republican about evidence-based anything? "It's all about the science" doesn't sound like anything I've heard the religious right shouting on Fox News. Besides, anyone who's remotely religious on those shows usually ends up being a nutcase who sacrifices their victims and strings them up to make murder-art installations. But I digress...)

Robert Kirkman aside, I don't think the zombie genre is about wish fulfillment for a post-civilization golden age. I think there's some complex reverse psychology at work here instead. The subliminal message being transmitted between every ammo-wasting headshot and every vehicle driven until empty, then discarded like all the other never-to-be-recycled trash, goes something like this: sure, there's a recession and healthcare is fucking expensive but just be happy you've got overpriced doctors to call any time of day or night. Sure, you might not be able to get an abortion in some states but at least you won't die in childbirth lying on the floor in a pool of blood while flesh-eating monsters beat down the door. Probably.

So on a certainlevel, the Zombie Apocalypse is great for Obama Care.

***

You want to know the single most implausible thing about The Walking Dead (yes, besides the zombies)? Nobody misses the Internet. I don't need to see them flopping around in a social media-withdrawal fueled malaise, but the Internet is so embedded in our every everything now that it's genuinely weird that you never hear anyone on the show acknowledge it.

["I miss the Internet." — Graffiti in the blockbuster zombie game "Left For Dead"]

Robert Kirkman comes right out and tells you what he thinks the Zombie Apocalypse is about on the back cover of every issue of The Walking Dead graphic novel:

"The world we knew is gone. The world of commerce and frivolous necessity has been replaced by a world of survival and responsibility. An epidemic of apocalyptic proportions has swept the globe, causing the dead to rise and feed on the living. In a matter of months society has crumbled: no government, no grocery stores, no mail delivery, no cable TV. In a world ruled by the dead, the survivors are forced to finally start living."