july  2013

2013

Closing arguments in the trial of Bradley Manning concluded on Friday and the judge says she will give 24 hours notice before announcing her verdict, which could come as early as Tuesday. The impending end of the court martial proceedings will bring to a close the legal chapter of a story that started three years ago with his capture and incarceration, much of which was spent in solitary confinement—or worse, a sort of extrajudicial limbo that resembles less the private cells of America's death row inmates than those of the detainees at Guantanamo or a military-flavored torture porn.

Closing arguments in the trial of Bradley Manning concluded on Friday and the judge says she will give 24 hours notice before announcing her verdict, which could come as early as Tuesday. The impending end of the court martial proceedings will bring to a close the legal chapter of a story that started three years ago with his capture and incarceration, much of which was spent in solitary confinement—or worse, a sort of extrajudicial limbo that resembles less the private cells of America's death row inmates than those of the detainees at Guantanamo or a military-flavored torture porn.

Soon after he was taken into custody an image took root at the back of my mind and has never left; the thought of this poor brave kid waiting alone in his cell for either justice or oblivion, while the rest of the world carried on voting and shopping and Tweeting and living our lives. He's 25 and his life is effectively over because he has to be made an example of to discourage others. Which is ironic because the vast majority of people don't really need to be discouraged from acting for the greater good. Most of us would never dream of doing what he did, were we ever—god forbid—in his position, having to choose between our terribly, terribly comfortable lives and our conscience.

I've also read the entire statement he made to the court in February, the one that wasn't supposed to be released but was diligently transcribed and published by journalist Alexa O'Brien. (A smuggled audio recording was later released by Democracy Now, but it's much harder to follow and impossible to excerpt.) The following passage is quoted from the section where Manning describes his reaction to the now-famous video of an aerial attack on a crowd of unarmed Iraqis, two of whom were later revealed to be Reuters employees, and his reasons for releasing the video to Wikileaks:

It was clear to me that the event happened because the aerial weapons team mistakenly identified Reuters employees as a potential threat and that the people in the bongo truck were merely attempting to assist the wounded. The people in the van were not a threat but merely "good samaritans." The most alarming aspect of the video to me, however, was the seemly delightful bloodlust they appeared to have.

They dehumanized the individuals they were engaging and seemed to not value human life by referring to them as quote "dead bastards" unquote and congratulating each other on the ability to kill in large numbers. At one point in the video there is an individual on the ground attempting to crawl to safety. The individual is seriously wounded. Instead of calling for medical attention to the location, one of the aerial weapons team crew members verbally asks for the wounded person to pick up a weapon so that he can have a reason to engage. For me, this seems similar to a child torturing ants with a magnifying glass.

...I hoped that the public would be as alarmed as me about the conduct of the aerial weapons team crew members. I wanted the American public to know that not everyone in Iraq and Afghanistan are targets that needed to be neutralized, but rather people who were struggling to live in the pressure cooker environment of what we call asymmetric warfare."

And I've been reading a lot of articles like this interview with Robert Meeropol, the youngest son of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. He was six years old in 1953 when his parents were sent to the electric chair after they were found guilty of giving nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union (although as the article says, "historians largely agree that there is no substantive evidence that... Ethel Rosenberg, engaged in any espionage at all"). A passionate advocate for free speech ( no pun intended, he's also a lawyer), he's founded the Bradley Manning Support Network, where you can sign Daniel Ellsberg's petition (hint) and get up to the minute information on the trial, of which Meeropol says, "The more people scream bloody murder, the better that is for Bradley Manning. I'm not sure it will make a difference... but that's all we can hope for."

While we're sending prayers to the patron saint to hopeless causes, you may as well join me in signing the Nobel Peace Prize petition. I know it's kind of tainted what with Henry Kissinger and President Obama being recipients and all, but it would be nice to see the prize awarded to someone who tried to prevent war crimes for a change, as opposed to committing them.

Speaking of Kissinger, until this weekend I had never really given Wikileaks more than a passing glance but for some reason today I got sucked in by The Kissinger Cables and spent over two hours this afternoon scanning the subject lines for juicy revelations. I found lots of stuff about Chile in 1973 that, had I the time or the energy to truly mine the vortex, I'm certain would have revealed hitherto unimagined dimensions in the banality of evil but as it stands, my search produced only random artifacts more bizarre than sinister. Exhibit A:

LIMITED OFFICIAL USE

27 JUL 73

FM AMEMBASSY SANTIAGO

TO SECSTATE WASHDC IMMEDIATE

SUBJECT: ROBERT F. KENNEDY, JR.

1. AP CORRESPONDENT JUST CALLED ME TO REPORT INCIDENT WHICH APPARENTLY INVOLVED ROBERT F. KENNEDY, JR. AT PORTILLO JULY 19. APPARENTLY MR. KENNEDY AND SEVERAL OTHER SKIERS WERE TAKING EXCURSION UP TO CHRIST OF THE ANDES ABOVE PORTILLO. SOME CHILEAN MILITARY PERSONNEL SAW THEM IN THE DISTANCE AND AFTER SOME SHOUTS OPENED FIRE ON THEM WITH SEVERAL SHOTS. FORTUNATELY, NO ONE REPORTEDLY WAS HIT. AP CORRESPONDENT'S SURMISE IS THAT CHILEAN BORDER TROOPS HAVE BEEN ALERTED TO POSSIBLE PATRIA Y LIBERTAD BORDER CROSSERS AND WERE EDGY.

2. COMMENT: I SAW KENNEDY MYSELF IN PROTILLO LAST SUNDAY (JULY 22), SO IF AP CORRESPONDENT HAS HIS FACTS RIGHT THERE IS NO REASON FOR CONCERN. SKIING TOUR UP TO THE CHRIST OF THE ANDES IS ADVERTISED AT THE PORTILLO HOTEL FOR STRONG SKIERS WHO CAN HANDLE POWDER SNOW, AND THERE IS NO REASON TO BELIEVE KENNEDY OR HIS PARTY WERE DOING ANYTHING IMPRUDENT. DEPARTMENT MAY WISH TO PASS THIS INFORMATION ON TO KENNEDY FAMILY AND REASSURE THEM. DAVIS

This was followed by a reply from the State Department that the Kennedy family had been notified of his safety. Four days later another cable from the Ambassador in Santiago continues to inform the State Department on Kennedy's whereabouts and speculates that "he would prefer to be left alone..." which might lead future amateur historians to wonder. Was the State Department concerned about RFK Jr.'s presence in Chile a mere two months before its planned overthrow of that country's elected government? Did they suspect the purpose of his visit had more to do with politics than powder? We may never know...

SUBJECT: ROBERT F. KENNEDY, JR.

ROBERT F. KENNEDY, JR. AND A FRIEND (ANDREW S. KARSCH) DEPARTED SANTIAGO THIS MORNING ON LAN 170 FOR BUENOS AIRES. THEY PLAN TO STAY APPROXIMATELY EIGHT HOURS IN BUENOS AIRES AND THEN TAKE ONWARD FLIGHT TO SAO PAULO WHERE THEY WILL BE STAYING WITH FRIENDS. MR. KENNEDY MADE NO REQUEST FOR ASSISTANCE. MY IMPRESSION IS THAT HE WOULD PREFER TO BE LEFT ALONE UNLESS FOR SOME REASON HE SHOULD CONTACT US. THEREFORE, THIS IS FYI ONLY. DAVIS

Another example of more-bizarre-than-sinister is a series of 1973 cables from the beleaguered Ugandan Ambassador. The political situation was deteriorating due to the increasingly paranoid and volatile behavior of then-dictator General Idi Amin. In one cable, the Ambassador offers a rather mixed message when advising the State Department on how to respond to recent conciliatory overtures from the General:

...BELIEVE THERE OUGHT TO BE SOME RESPONSE... FOR IT WOULD NOT HELP OUR GENERAL SITUATION TO BE ENTIRELY UNRESPONSIVE TO HIS EFFORT TO PATCH THINGS UP A BIT. AT SAME TIME BELIEVE AMIN IS ONE OF THOSE CASES WHERE IF ONE HAS HIM AS A " BEST FRIEND" ONE DOES NOT NEED AN ENEMY. KEELY"

And a few days later, regarding another apparently inflammatory telegram sent by the General to President Nixon, he offers the following advice:

IN VIEW INSULTING CONTENT AND NOXIOUS TONE OF TELEGRAM, SUGGEST MOST DIGNIFIED RESPONSE WOULD BE TO IGNORE IT."

It was a summer day about five to seven years ago and I was walking home from work when I saw the most amazing car idling at the crosswalk. It was big and old and black and awesome, like something out of Dick Tracy or The Godfather (Part One) and in the 10 seconds or less that it took me to approach it from the side and cross the street in front of it, I struggled to imprint the distinctive outline on my memory. The hood was long and impressive, like a pre-WWII era Rolls Royce or Dusenberg. The wheel wells were outsized and curvaceous, and flanked a long standing rail on both sides. I scanned the length of the vehicle for details that would identify its maker but could discern no recognizable markings.

It was a summer day about five to seven years ago and I was walking home from work when I saw the most amazing car idling at the crosswalk. It was big and old and black and awesome, like something out of Dick Tracy or The Godfather (Part One) and in the 10 seconds or less that it took me to approach it from the side and cross the street in front of it, I struggled to imprint the distinctive outline on my memory. The hood was long and impressive, like a pre-WWII era Rolls Royce or Dusenberg. The wheel wells were outsized and curvaceous, and flanked a long standing rail on both sides. I scanned the length of the vehicle for details that would identify its maker but could discern no recognizable markings.

Passing in front of its imposing steel grill, I could see no hood ornament, logo or insignia; no make or model stamped conveniently in steel lettering. In the second or two we spent eye to headlamps, I captured a single mental snapshot that in the moments, months and years to follow would variously be remembered as the clearest, most distinguishing and irrefutable detail, and the most contentious, questionable and corruptible, prone to second-guessing and eventually, suggestion.

I saw the number eight staring out at me from the middle of the grill. That was the one thing I was sure of, as I hurried home to Google the rapidly-disintegrating memory. Certain that I was no more than a few search result pages away from pinpointing the make, model and year to replace the hazy mental image that was at that very instant starting to jostle like a fidgety child made to stand in line. But the synapses I had temporarily assigned had already begun rearranging themselves diabolically—they danced around, refusing to be tagged as image or object, switching places in a game of quantum hide and seek as I fumbled with my keys. I finally arrived home, bursting through the door a chaos of greetings and grocery bags, and made a beeline for my computer, a flurry of words expelling themselves in rapid-fire, unorganized explanation.

I saw the number eight staring out at me from the middle of the grill. That was the one thing I was sure of, as I hurried home to Google the rapidly-disintegrating memory. Certain that I was no more than a few search result pages away from pinpointing the make, model and year to replace the hazy mental image that was at that very instant starting to jostle like a fidgety child made to stand in line. But the synapses I had temporarily assigned had already begun rearranging themselves diabolically—they danced around, refusing to be tagged as image or object, switching places in a game of quantum hide and seek as I fumbled with my keys. I finally arrived home, bursting through the door a chaos of greetings and grocery bags, and made a beeline for my computer, a flurry of words expelling themselves in rapid-fire, unorganized explanation.

As luck would have it (or as it turned out, maybe not) Mr. Pink was not home alone, but in the company of the one friend we have with an encyclopedic knowledge of automobiles. It took me no time at all to ignite his curiosity as well as Mr. Pink's, and before long the three of us were engaged in separate yet similar quests toward a common goal: find that car.

I made a little drawing, an attempt to set down the few details I clearly remembered before looking at any others. I knew all too well that the features I'd stored in my mind were as good as interchangeable with the millions I hadn't seen—but then I quickly realized I can't draw cars. It looked ridiculous... a giant grill, two goofy, disconnected headlamps and the number eight floating above or between them (it was suddenly impossible to recall exactly where I'd seen it). If I could find the drawing, I wouldn't hesitate to scan it in now and post it here for the laugh. (I know I kept that scrap of paper, it's just a matter of where...)

I proceeded to search database after database of hood ornaments, emblems and insignias and became increasingly uncertain that there had even been one. I spent hours scrolling through countless screens, scanning an entire century of steel and speed. Vast untold thousands of thumbnail images seared themselves into my retinas, bypassing random access memory, an entire history of the combustion engine rendered a categorized chaos of similar images, fractal and fragmentary.

I proceeded to search database after database of hood ornaments, emblems and insignias and became increasingly uncertain that there had even been one. I spent hours scrolling through countless screens, scanning an entire century of steel and speed. Vast untold thousands of thumbnail images seared themselves into my retinas, bypassing random access memory, an entire history of the combustion engine rendered a categorized chaos of similar images, fractal and fragmentary.

I won't bore you with all the details of those first forays into the history of wheeled transport, the eventual descent into worlds of automotive minutiae theretofore unknown to me. But suffice it to say that it wasn't until this very week that I finally achieved some semblance of peace, identifying if not the actual make and model (Tudor V8 or Model 40), at least the manufacturer (Ford) and, if not pinpointing the exact year, at least placing it within a very narrow range between 1933-1936. The key that unlocked the labyrinth in my mind, which I'd constructed around an ephemeral shred of memory and tried so valiantly to cement and preserve all those years, was none other than Craigslist.

I won't bore you with all the details of those first forays into the history of wheeled transport, the eventual descent into worlds of automotive minutiae theretofore unknown to me. But suffice it to say that it wasn't until this very week that I finally achieved some semblance of peace, identifying if not the actual make and model (Tudor V8 or Model 40), at least the manufacturer (Ford) and, if not pinpointing the exact year, at least placing it within a very narrow range between 1933-1936. The key that unlocked the labyrinth in my mind, which I'd constructed around an ephemeral shred of memory and tried so valiantly to cement and preserve all those years, was none other than Craigslist.

This could very well be the actual vehicle I saw that day (and it's for sale!). Can I get a hallelujah for the miracle of Craigslist?

(Oh, and wish me and Mr. Pink a happy anniversary—15 years!)

I've been reading about the newest controversy in "emotion science," the branch of psychology devoted to the study and analysis of how human emotions are revealed through facial expressions. At issue is whether these external indicators are in fact universal—as demonstrated by the research of Paul Ekman (via Malcolm Gladwell)—or, as Northeastern University Professor Lisa Barrett argues, if "each of us constructs [emotions] in our own individual ways, from a diversity of sources: our internal sensations, our reactions to the environments we live in, our ever-evolving bodies of experience and learning, our cultures."

I've been reading about the newest controversy in "emotion science," the branch of psychology devoted to the study and analysis of how human emotions are revealed through facial expressions. At issue is whether these external indicators are in fact universal—as demonstrated by the research of Paul Ekman (via Malcolm Gladwell)—or, as Northeastern University Professor Lisa Barrett argues, if "each of us constructs [emotions] in our own individual ways, from a diversity of sources: our internal sensations, our reactions to the environments we live in, our ever-evolving bodies of experience and learning, our cultures."

At the heart of the debate is Ekman's research, conducted in the 1960s and cemented in the public consciousness by Malcolm Gladwell's Blink, in which he showed a series of faces expressing the seven basic emotions (anger, contempt, disgust, surprise, sadness, happiness and fear) to people all over the world and found that, regardless of race, culture, language or social status, people could identify the emotions correctly and thus they concluded that emotions are universal and quantifiable (I'm not sure how they extrapolated the latter from the former, but then I haven't read the study, only the Gladwell). But given the sudden boost in prestige that comes with a mention in a runaway best-seller, the sudden interest of government agencies and Hollywood studios and the multimillion-dollar offers that follow, I suspect a lot of theories based on common sense and extrapolated from controlled laboratory experiments could suddenly be made to seem quantifiable.

50 years later, however, it seems there's a backlash. The Department of Homeland Security, having spent $878 million putting Ekman's deception-detection techniques to the test in America's airports, recently reported that although thousands of arrests have been made since their adoption in 2004, the program hasn't caught a single terrorist. Also it's been running under constant criticism for being a thinly-disguised system of racial profiling based on dodgy science and which, if not actively harmful, is at best useless in practice (and here I thought they put the last nail in the coffin of that theory with the cancellation of Lie to Me).

In the Boston Magazine article, Professor Lisa Barrett contends that Ekman's original study doesn't prove what it claims to because when they showed people photos of the seven expressions, they provided a multiple-choice selection of emotions to label them. Participants were asked to match the emotions expressed in the photos with words like "happy" or "angry" or stories that were obviously sad or frightening, etc. Barrett recently restaged the same experiment with an isolated tribe in southern Africa, only without the labels, and found they were unable to replicate the results that had supposedly proven Ekman's hypothesis:

Quote: "...Smiling faces went into one pile, wide-eyed fearful faces went into another, and affectless faces went mostly into a third. But in the other three piles, the Himba mixed up angry scowls, disgusted grimaces, and sad frowns. Without any suggestive context, of the kind that Ekman had originally provided, they simply didn't recognize the differences that leap out so naturally to Westerners."

(Oh, for what it's worth, Barrett's researchers pared it down to six emotions, either discarding contempt or combining it with disgust, perhaps because they couldn't tell the difference.) So this is where I have to call bullshit. Do the differences between "angry scowls, disgusted grimaces, and sad frowns" really leap out so naturally to Westerners? I'm about as Western as you can get and, although I usually score better than average on emotional intelligence tests, I think it's highly disingenuous to suggest that to Westerners the difference between expressions of anger, disgust, contempt and sadness naturally leap out at us. Setting aside the "epidemic" levels of autism and the 1-2% of the population that may be psychopathic and therefore clinically incapable of gauging other people's emotions, the very question sets up a false—or at any rate, questionable—dichotomy between what are in reality fluid, often interchangeable—and even more often coexistent—states of mind.

Add to that ambiguity the fact that most of the time when we witness a genuine expression of one of those negative, antisocial emotions, there's going to be some simultaneous attempt on the part of the person expressing it, to hide or disguise their true feelings. Your boss may be furious when you openly disagree with her in a team meeting but the office code dictates that she treat you with a modicum of professionalism, so you may only catch a fleeting glimpse of her anger. Naked, unadulterated expressions of pure anger, disgust, sadness and contempt—despite a decade of reality TV—are rarely directly expressed in Western, or to put it more accurately, civilized society without a dozen other emotions crowding the edges, competing for face-time, as it were, and muddying the waters.

The Himba tribe categorized happy and frightened faces correctly, same with most of the "neutral" faces, which corroborates the original experiment. In the early 60s, there was no World Wide Web connecting friends and coworkers to like-minded individuals around the world, no "translate this page" enabling teenagers to read each other's blogs and find their innermost thoughts echoed by teenagers in the most distant and different of places. When Ekman began his study, the US had yet to pass the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts that mandated equality and legal protection for minorities. What seems to us unquestionable, that we are all one human family and that race is merely an artifact of ancient human migration patterns, a set of classifications more useful in emphasizing superficial differences and justifying the oppression of various groups for political gain than anything to do with science or identity, were not yet truths that everyone held self-evident—not by a long shot.

The Civil Rights era was also the peak decade of the Cold War, when science was being used to fortify Western nations against other Western nations, resulting in a climate of such fear and mistrust that some 20 years later Sting would feel the need to remind Americans that "we share the same biology regardless of ideology" (and even he stopped short of making an unqualified pronouncement; "I hope the Russians love their children too"). So in its context, Ekman's research came along at a crucial time in history, proving that emotions were the universal currency of human interaction and assuring people that a smile in Denmark was the same as a smile in Zimbabwe. While it may seem obvious to us—even a bit too easy—at the time, that assurance and others like it probably helped lay the foundations for the socially connected, colorblind world we like to believe we inhabit today.

Back to the idea that Westerners are better equipped to differentiate sad faces from angry faces. It goes without saying that we in the modern "West" exist in perpetual immersion in other people's emotions. Every day we're surrounded by their mind-numbing proliferation, from the constant overshare of our friends' mental states on Facebook to the exploitation of celebrity dysfunction as the media's prevailing business model, and somewhere in between is the vast emotional dumping ground that is reality television.

This is purely speculation on my part, but isn't it possible that the Himba simply haven't yet developed the specific social context in which it would be necessary to understand the difference between an expression that says, "I have to be home by 10:30? Are you freaking kidding me? I said freaking, dad—geez, chill out, okay? God, this is so. unfair. None of my friends have a curfew. Why do I have to be the only one whose parents are total prehistoric assholes?" from an expression that says, "Oh my god, you cannot be serious. Kevin told Jason to tell you that he likes me? Isn't he that weirdo who wears a parka even when it's like 80 degrees out? I am totally going to die. That is so. gross."

What if the researchers came to you and said there are six categories of human emotion; tell us what they are and sort this pile of 100 expressions into your six categories. Would you have named the same six? Where would you put a confused expression? A seductive, come-hither gaze? How about a look of awe or astonishment? It's obvious when you give it just a bit of thought that emotions are not discrete modes of functioning or isolated mental states that can be quantified, treated or judged for whatever purpose is footing the bills.

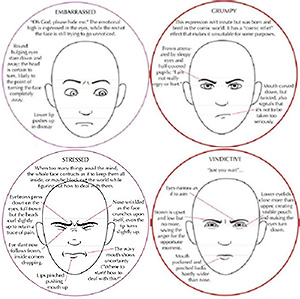

A few weeks or months ago, I stumbled across this amazing chart of facial expressions created by Joumana Medlej as a resource for fellow artists. Its stated purpose is nothing grander or more subversive than demonstrating how the vast, ephemeral range of human emotions can be distilled and conveyed convincingly by a stylized combination of economical lines. Anyone who has taken a life drawing class knows that just as important as the marks you make on the page is the radical simplification of visual data that your brain must perform in order to render your subject in two dimensions. As your hand creates the simulation, your eye is constantly taking in information which you must decide whether to incorporate or ignore; discarding perceptions of volume, distance and depth while documenting the range of light and shadow to convincingly convey edges, curves and foreshortening.

A few weeks or months ago, I stumbled across this amazing chart of facial expressions created by Joumana Medlej as a resource for fellow artists. Its stated purpose is nothing grander or more subversive than demonstrating how the vast, ephemeral range of human emotions can be distilled and conveyed convincingly by a stylized combination of economical lines. Anyone who has taken a life drawing class knows that just as important as the marks you make on the page is the radical simplification of visual data that your brain must perform in order to render your subject in two dimensions. As your hand creates the simulation, your eye is constantly taking in information which you must decide whether to incorporate or ignore; discarding perceptions of volume, distance and depth while documenting the range of light and shadow to convincingly convey edges, curves and foreshortening.

I remember one moment in my first year drawing class when this concept demonstrated itself to me in the form of a model's profile. She was facing the window and as I started to trace the outline of her face I realized that what I was attempting to render in black charcoal had the exact opposite appearance in real life. The "edge" that so clearly defined her features against the backdrop of the classroom behind her was actually the brightest part of her face, reflecting the light of the sun the same way the glowing curve of the moon stands out against the night sky. I stared at her profile for quite a while that morning, as if seeing the human face for the first time, before finally turning back to the page and consciously committing to the radical simplification I had always performed automatically until that moment.

As Joumana Medlej explains, "In drawing facial expressions, we have to bypass 'what a sad face would look like' and aim for 'how we would recognize a face as being sad.' This is because an illustration must make up for the loss of other clues that we have in real life to decipher someone's mood, many of which we perceive unconsciously. In real life, we just know..."

This is demonstrated in the sparse but completely effective emotions expressed through the stylized curve of a single eyebrow in the chart above, and it's communicated with brilliant brevity by cartoonists on the faces of characters from Cruela De Vil to Sponge Bob Square Pants. Kids can easily tell the difference between the lonely, wistful Wall-E and the lovestruck, slightly intimidated Wall-E and he doesn't even have a face.

This is demonstrated in the sparse but completely effective emotions expressed through the stylized curve of a single eyebrow in the chart above, and it's communicated with brilliant brevity by cartoonists on the faces of characters from Cruela De Vil to Sponge Bob Square Pants. Kids can easily tell the difference between the lonely, wistful Wall-E and the lovestruck, slightly intimidated Wall-E and he doesn't even have a face.

Of course emotions are complex and confounding, a set of variables shared by all but interpreted differently by each individual to the point that even siblings and old married couples who've grown to look alike over the decades, can't read the unspoken, enigmatic truth in each other's faces 100% of the time. Despite that, and in spite of the continuing efforts of emotion scientists periodically splintering off into warring factions unable to see they're merely describing none-too-distant points on the same continuum, don't we all just intuitively know this stuff?

I think emotion science failed when it tried to make the cognitive leap from asserting that broad, basic categories of emotions—your happiness, anger, fear, sadness—are universal (and all the evidence indicates they still are) to the claim that you must therefore be able to tell when someone is lying—and not just someone, everyone, or a statistically significant percentage of people most of the time. Lying isn't an emotion, first of all. It isn't even consistently associated with the same emotions for everybody in a given culture. Also, everybody lies. Even if you were somehow able to isolate "dishonesty" from the myriad competing expressions, circumstances and motivations playing across our faces at any moment, what then? Detecting a lie doesn't point you to the truth. If you pulled 100 "liars" out of the Departures line every hour you would then be faced with the impossible task of ferreting out 100 different reasons for lying. Many of them would be personal, some would even be subconscious, and a number would invariably be so deeply private that the very act of probing could provoke a defensive, even destructive response. And maybe—probably, evidently—none of them would have a thing to do with terrorism.

But just as culture shapes our range of emotional perceptions, it creates its own blind spots as well. Imagine the generation of young men shipped off to war in Europe who endured years of separation from their wives and girlfriends during the critical emotional bonding phase of their relationships. Communication back home from the front was limited to brief, infrequent calls made from not-so private phone booths, written letters and postcards that were probably screened by military censors but definitely self-censored because letters from overseas tended to get shared around, and who wanted to imagine their girlfriend's mother (or his own, god forbid) reading his letters and unwittingly being exposed to all manner of smutty thoughts? The combination of emotional distance and the abundance of prostitutes overseas (if we're being honest) bred a whole generation of men who couldn't tell the difference between an expression of loving contentment and one of bored tolerance in exchange for financial security—and the cultural fallout from this inability became evident in a generation of Betty Drapers, the housewives in gilded cages immortalized by The Rolling Stones' in "Mothers Little Helper."

But just as culture shapes our range of emotional perceptions, it creates its own blind spots as well. Imagine the generation of young men shipped off to war in Europe who endured years of separation from their wives and girlfriends during the critical emotional bonding phase of their relationships. Communication back home from the front was limited to brief, infrequent calls made from not-so private phone booths, written letters and postcards that were probably screened by military censors but definitely self-censored because letters from overseas tended to get shared around, and who wanted to imagine their girlfriend's mother (or his own, god forbid) reading his letters and unwittingly being exposed to all manner of smutty thoughts? The combination of emotional distance and the abundance of prostitutes overseas (if we're being honest) bred a whole generation of men who couldn't tell the difference between an expression of loving contentment and one of bored tolerance in exchange for financial security—and the cultural fallout from this inability became evident in a generation of Betty Drapers, the housewives in gilded cages immortalized by The Rolling Stones' in "Mothers Little Helper."

I suppose it would be fair to ask if the parents of today are breeding a generation of children who will lack the ability to differentiate between an expression of genuine interest and one of annoyed anticipation of getting back to Gears of War or America's Top Model. But it's probably too soon to say.

A final note on the inherent limitations of classification systems, also courtesy of Mindhacks: In a short passage from Otras Inquisiciones, Jorge Luis Borges quotes an apocryphal taxonomy from "a certain Chinese dictionary entitled The Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge. In its remote pages it is written that animals can be divided into (a) those belonging to the Emperor, (b) those that are embalmed, (c) those that are tame, (d) pigs, (e) sirens, (f) imaginary animals, (g) wild dogs, (h) those included in this classification, (i) those that are crazy-acting (j), those that are uncountable (k) those painted with the finest brush made of camel hair, (l) miscellaneous, (m) those which have just broken a vase, and (n) those which, from a distance, look like flies."